“A Matter of Truth”

The Northeast Slavery Records Index is advancing slavery-related research and education

Author: Michael Friedrich

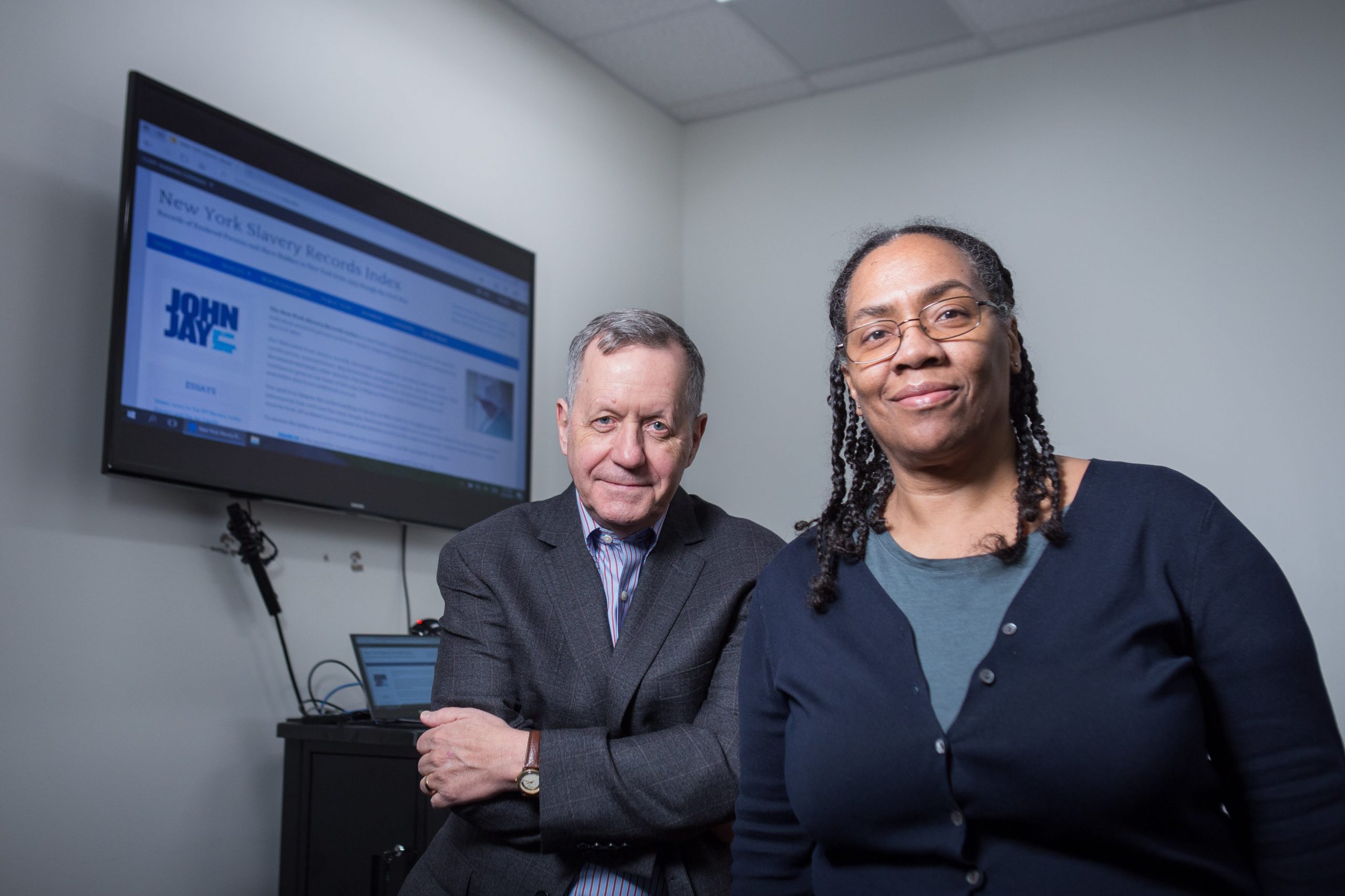

Most people don’t associate the American Northeast with slavery, but the region is marked by a deep history with the loathsome institution. With the Northeast Slavery Records Index, or NESRI, John Jay College faculty Dr. Ned Benton and Dr. Judy-Lynne Peters have created a database to help document that history. “There was a tremendous amount of slavery in the Northeast,” Benton said. “As a matter of truth, we need to flesh out the story.”

Their project aims to shine a light on the humanity of the many enslaved people in the Northeastern states who long went unrecognized. “We have been able to identify thousands of people who history did not record, who had no voice,” Peters said. “We are in a position to tell their stories, identify where they lived and died, and hopefully connect them to their descendants.”

NESRI, a collaboration with institutions across the Northeastern states, is run by a faculty-student team at John Jay. Students help with the research, indexing records that relate to enslaved people—an experience that can be deeply moving for them. “It brings together their value of being a fierce advocate for justice, their sense of outrage at the things that are true of history, and the research skills they’ve learned in their studies in a way that many students don’t experience during a college education,” Benton said.

Valencia McMillan, a John Jay alumna who worked on the NESRI database in 2017, indexed financial records related to the release of enslaved people; she discovered instances in the records where enslavers were able to profit off of the abandonment of children born to enslaved mothers. “I felt a lot of things—angry, obviously,” said McMillan, who is Black. “But I also felt intrigued that these records still existed. It was exciting to make connections.”

The Northeast struggled to eliminate slavery, and that history is embedded in the region. That includes New York City, where slavery began when Dutch ships landed carrying enslaved people. NESRI data show that in the 1790 census, fully one-third of Brooklyn residents were enslaved. Many Brooklyn streets are named after prominent enslavers. Born to a family that held slaves and invested in the slave trade, college eponym John Jay himself kept humans as property. Jay’s legacy is complicated; he also spent many years advocating for the abolition of slavery and, as governor, he signed the Gradual Emancipation Law of 1799, which began the end of slavery in New York.

Similar histories can be found in many cities and towns across the Northeast. Through their investigations, NESRI staff have compiled previously unknown records about such towns. Benton and Peters stress that the database’s uses are broad. “We are doing basic digital history research that will empower people in the future to do all kinds of study,” Benton said.

Some of that study is happening today at John Jay. In 2021, the college’s Office for the Advancement of Research and Office of Undergraduate Studies announced a new award for faculty members that supports scholarship, creative endeavors, and curriculum development projects that rely on NESRI data. The 2022 award winners include Victoria Bond, Professor of English, who is working with students to design a curriculum for primary school students that teaches composition as a means to relay histories of slavery. Roberto Visani, Professor of Art, is collaborating with students to create unique cardboard sculptures that incorporate imagery from NESRI of enslaved people, to be displayed throughout the college. And Dr. Michael Pfeifer, chair of the History department, designed a curriculum in which students use NESRI to learn about enslavement and the roots of racism in the region, culminating in a collective presentation.

All this is only a beginning. Benton and Peters said that in the coming years the data will help communities come to grips with local enslavement. NESRI staff are creating systems for counties, cities, and towns to look at region-specific records, and writing articles about how communities can publicly acknowledge the harms of the past. The data also have genealogical implications, and the faculty-student team is working on coding family structures into their data sets—an effort to help users who are seeking relatives and telling lost stories about enslaved people. These endeavors will be supported by a nearly $100,000 Digital Justice Grant from the American Council of Learned Societies.

“When we started this, we had no idea how people would use it,” Peters said. “Now I’m discovering people’s ideas about how to use it, and I find it amazing.”

IMAGES:

A Ride for Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves (Eastman Johnson, 1862) Gift of Gwendolyn O. L. Conkling, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum

Cardboard sculpture of A Ride for Liberty (Roberto Visani) Photo credit: Erin Jenkins, courtesy of Brattleboro Museum & Art Center