Once-Buried Histories Made Visible

John Jay Professors Reclaim Art History in the Heart of Manhattan

Featured Faculty: Claudia Calirman, Bettina Carbonell, Lisa Farrington, Erin Thompson, Thalia Vrachopoulos

By: Fisayo Okare

For too long, the history of art has been told through a narrow lens, silencing the voices and stories that don’t fit into the mainstream narrative. At John Jay, a new cohort of scholars is determined to rewrite the story. Recognizing the injustice in the narratives that have dominated art history for decades, they are reshaping our understanding of art and its place in society, reclaiming space for those whose stories have been erased.

THE UNKNOWN MUST BE KNOWN

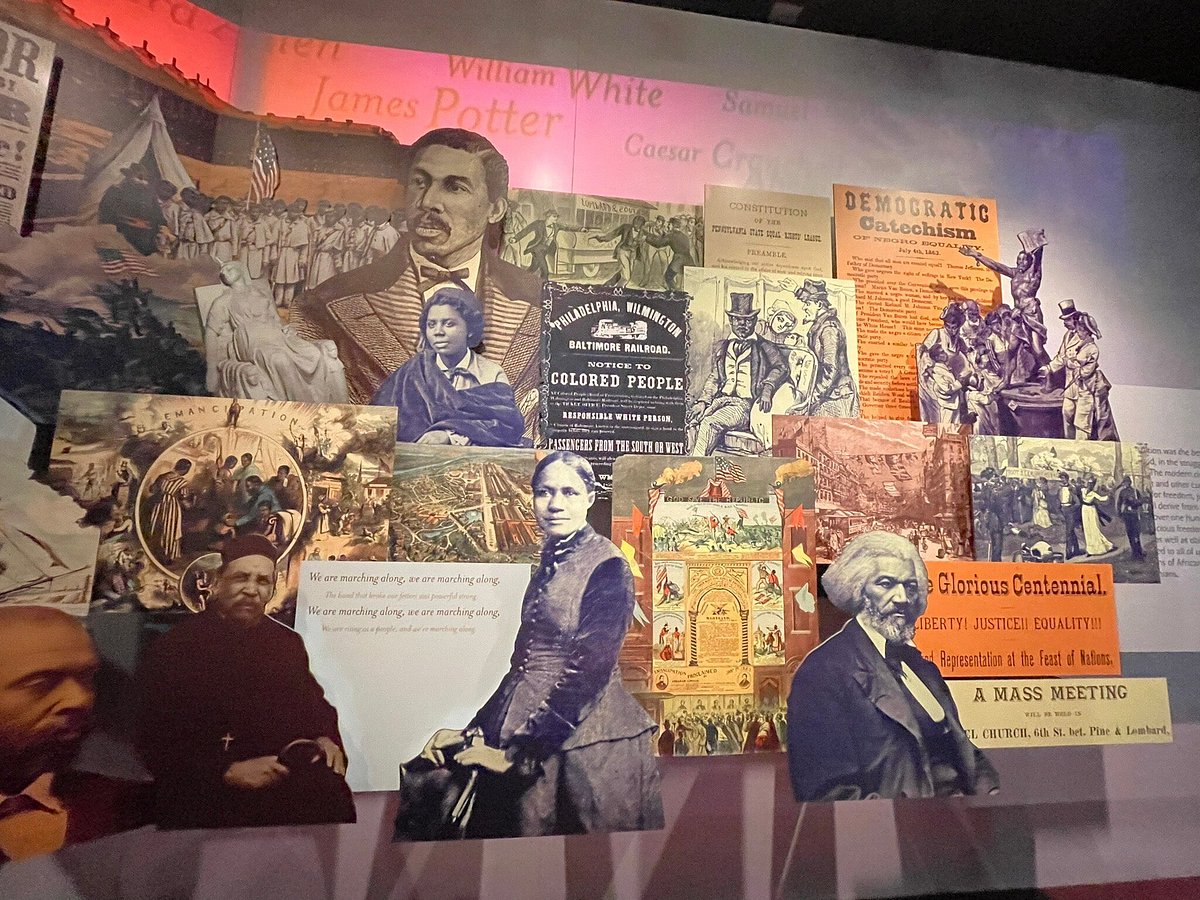

Beginning more than twenty years ago, and in preparation to write her 2023 book, Consequential Museum Spaces, Carbonell immersed herself in decades of literature on museum studies. She observed that the field seemed slow to embrace the growing emphasis on diversity and equity in other disciplines. Many of the people she spoke to about African American museums were unaware that they existed, she says. However, that changed when the National Museum of African History and Culture began to take shape in public discourse, and eventually materialized as a physical building.

The book was born out of her growing interest in the gradual emergence of the national museum, but it did not stop there. Carbonell then searched for evidence of other African American museums and found gaps in the narratives about them. Sometimes, she found nothing—a journey that ultimately inspired the creation of her book. The result is a book that vividly documents her observations, analyzes relevant literature, and argues for increased interest in the subject matter. She writes in it that African American museums do more than just exhibit artifacts; they offer a corrective lens on history.

“When you see objects given that museum effect, highlighted and put in a glass case, and people look at them, read the label, and learn more about the object, who made it and how it was used, suddenly that particular artist and that culture becomes more real and more important,” Carbonell says.

Carbonell’s work is part of a broader push at John Jay to present art history in a way that amplifies visibility and helps people understand the importance of representation. Similarly, Distinguished Professor of Art Dr. Lisa Farrington also seeks to spotlight African American history and give greater context and meaning to its culture and art.

ENHANCING VISIBILITY IN ART HISTORY

While writing her book, African American Art: A Visual and Cultural History, Dr. Farrington aimed to integrate African American art into the broader canon of American art. Rather than giving the chapters of her book names such as ‘slavery,’ and ‘post Reconstruction’—titles that do not directly highlight the creations of Black artists—she instead sorted artists based on the style of their art. So there are chapters on federalist art, romanticism, and neoclassical style. Farrington knows of just one other book before hers that had taken this approach. She says doing this was important to expose the world and art historians to the works of African American artists. “I have friends who are White scholars who couldn’t navigate how to translate information from a book on Black art into their own survey texts on (mostly White) American art. The chapters didn’t line up. The subject matter didn’t line up,” Farrington says. “So when they are trying to write about Federalist art in a book on African American art, it might be called slave art.”

Similarly, Farrington’s forthcoming book, The World Before Racism, has been designed to appeal to a wide audience. Anyone from age 10 to 90 will find the book accessible, she says. “It is a picture book as well as a revealing history lesson, deliberately designed to reach the broadest possible audience. This is probably going to be my magnum opus, my greatest work, and the most effective because my books up to now have affected the Black community for the most part. This book is designed to preach to people outside of the Black community, to try to show them that racism is really a construct, by showing them irrefutable proof,” Farrington says.

The World Before Racism tells a visual story about the truth about racism, and the fact that Blacks and Whites were friends for centuries before the modern era. Farrington has been advancing that particular subject as a lecture over the last 20 years. “It’s a kind of lecture that caused people to walk out in tears, stumbling in the wrong direction from their house because it had so much information in it that was shocking to both Blacks and Whites. Art is a hard-to-refute primary source but, sadly, people just don’t go to primary sources anymore,” she says.

JUSTICE THROUGH ART HISTORY

John Jay faculty invite readers to engage deeply with the transformative power of art in shaping collective understanding and societal change. Take for instance the work of Dr. Erin Thompson, Professor of Art Crime at John Jay College, whose recent book Smashing Statues explores the lesser-known history of public monuments in the United States, particularly those that bolster a narrative of triumphant whiteness throughout American history. What are the stories these artifacts tell, versus the hidden stories behind their origins? And when those stories come to light, who decides whether they stay or go, and how are the decisions to reshape common spaces made? Thompson provides essential context to understand the ongoing controversy over whose voices are represented, and what types of history are venerated, in monumental art.

The origins of Thompson’s book date to August 2020, when a video surfaced on Twitter showing someone trying to pull down a statue in Saint Paul, Minnesota, with a rope. She retweeted the video, horrifying some who thought it impossible that a professor who studied the history of the deliberate destruction of cultural property could condone such an act; the tweet went viral. “But what was interesting to me was that thousands of people were asking questions in the responses,” Thompson says. “I realized there was just a lot that, frankly, White people and White Americans don’t know about monuments, the history, their current effects, and the attitude of other Americans toward them.”

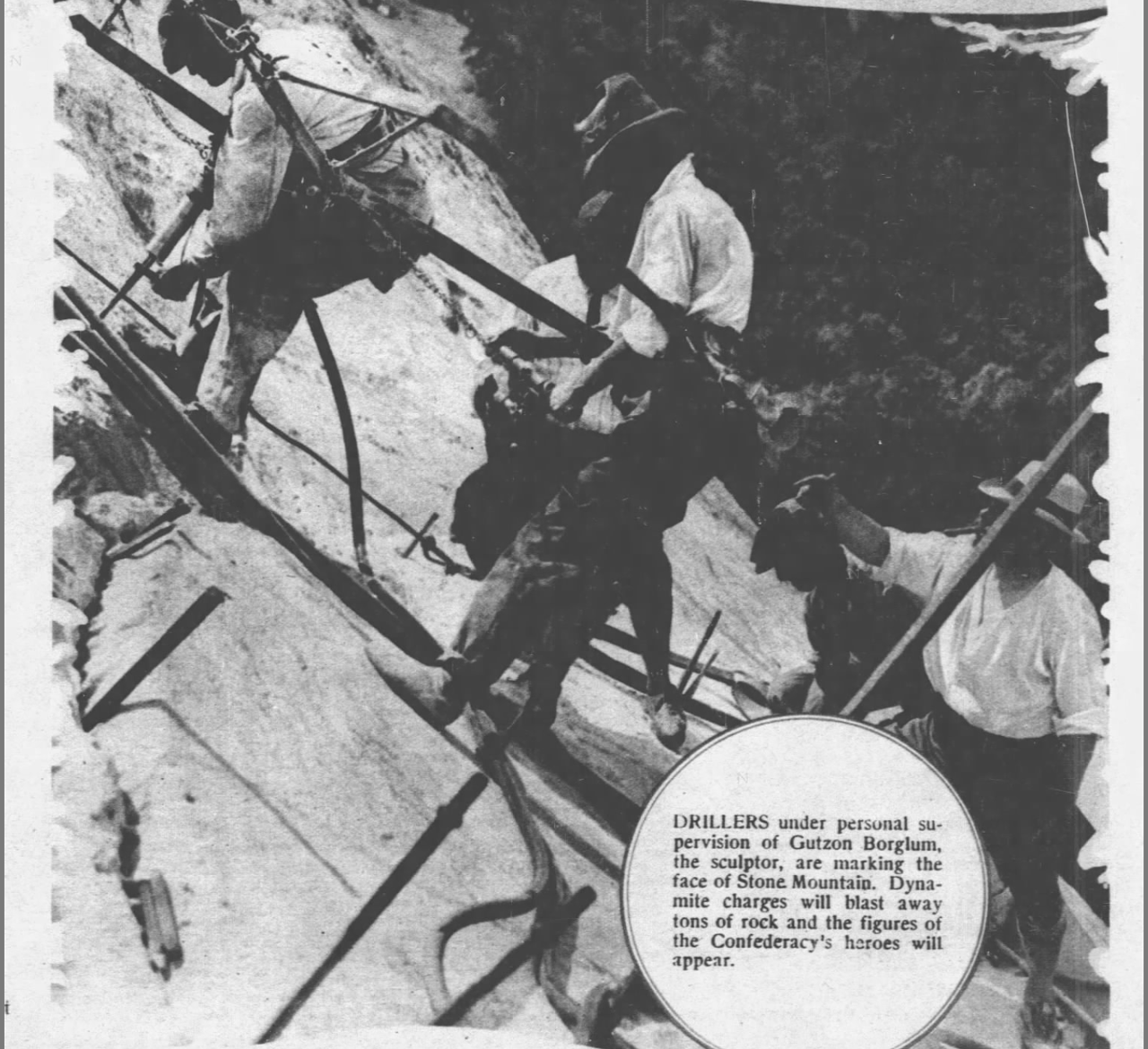

One of Thompson’s goals for the book is to “act as a resource for people who are doing campaigns to change monuments”—a goal which is already being fulfilled. There’s a movement, the Stone Mountain Action Coalition, dedicated to modifying Stone Mountain, the world’s largest Confederate monument, which she featured in her book. In Smashing Statues, Thompson uncovered the historical fact that a lot of the work on the state park—which houses the Stone Mountain monument—was performed by prison labor; a mostly Black labor force involuntarily created a memorial to the Confederacy. While campaign leaders were initially unaware of that aspect of history, notes Thompson, it has become a key part of their materials advocating for the monument’s revision.

Thompson was present for the melting down of the Robert E. Lee statue from Charlottesville, which she had also highlighted in her 2022 book. This statue sparked controversy in 2017, and Thompson tracked the political process and legal battles that led to its eventual removal.

Statues often blend into the background, much like street furniture. They remain unnoticed until strong emotions like hatred or love bring them into focus. “So many debates about monuments, museums, and censoring artworks are very heated emotional debates about the theory of all of these things,” Thompson says. “I want to say, okay, you can have your political and cultural positions, but here are some facts and information to help us decide better.”

ART ITSELF CAN REVEAL HISTORY

In addition to being home to faculty whose work reveals heretofore unknown narratives in art history, John Jay also houses the Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery—a fine art gallery heavily focused on social issues and the humanities through artworks.

In 2014, Dr. Thalia Vrachopoulos, Professor of Visual Arts at John Jay, curated an extraordinary showcase at the gallery called Assenting Voices: Agitprop Art in North Korea. It’s unusual to have an exhibition on North Korean art in the U.S. In fact, the collection of art showcased in the show had to be routed through China. Finally in New York, displayed at John Jay, the art collection helped observers look at a style of social realism in art usually taken up by dictators. “Mussolini, Stalin, Hitler, liked this kind of art, which is propaganda art,” Vrachopoulos explains. “Art that is design-oriented, has a sharp edge, and only the best of that society is depicted. Nothing negative is allowed into these images. Everything you see is to glorify the state.”

The exhibition featured works that portrayed society as harmonious and perfect. “All appears well and good in a society that killed 20 million people, for example, with Stalin. And with Hitler, who killed six million Jews. You didn’t see any of the negative, the camps, the ovens, the horror that went on. That’s why I called it Agitprop art,” Vrachopoulos explains. “I was so proud that we were so open-minded to be able to show something like this at John Jay. It wouldn’t have been possible elsewhere, I don’t think,” Vrachopoulos said.

Indeed, the show had a lasting impact. It led to a fellow art historian, Dr. Soojung Hyun, reaching out to Vrachopoulos for a collaborative show in 2022, Blood and Tears, about the 1980 student revolt in South Korea, wherein almost 3,000 students were killed because of the reactionary government. The show, at the Shiva Gallery, was funded by the Gwangju government, which paid for shipping the artwork, the opening reception, and the catalog.

This exhibition is one of many impactful shows at the Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery, aimed at encouraging John Jay students and other visitors to reflect on art and its significance.

KNOWLEDGE GAINED

The idea of what art is can seem narrow to many people, says Department Chair and Associate Professor of Art History Claudia Calirman. Art is just beauty, students often say in their first days of attending an art history class at John Jay. But with the caliber of work John Jay faculty do, little wonder that, by the time students complete their classes, their horizons are broadened. Art can be used as a social tool, can be transformative, and can be used for social justice. “They leave with a lot of baggage that I’m sure they didn’t come with,” Calirman says.

Art is instrumental not just in changing the world but also showing the possibilities of change. For many John Jay students, once they understand an artwork and its historical context, this empowerment enables them share their insights with friends, act as informal tour guides, and help others appreciate and understand the art.

“There’s a lot of fight for social justice in the art world. We try to bring that to discussions that relate to what students are interested in,” Calirman explains. “As a Chair, that’s my goal: to integrate each time, more and more, the idea of art with social justice, art with criminology, and so many things.”