Policing

Big

and Small

Evidence-based, data-driven approaches

to policing can help improve

effectiveness and accountability

BY CHASE BRUSH

RESEARCHERS: PREETI CHAUHAN,

PHILLIP ATIBA GOFF,

CHRISTOPHER HERRMANN AND ERIC PIZA

Today, Compstat, as the system came to be called, remains one of the first major efforts by police to take a more scientific approach to the job, an early example of officers using real data and statistics to make evidence-based decisions about how, when, and where to tackle crime. Rather than rely on theory or tradition to inform practice, Compstat forced departments to think critically about their work and whether it was, simply put, actually working.

This concept — the “what works” model of policy — is known as evidence-based policing, and it’s become a guiding principle for members of police and academic circles looking to further improve the practice in the 21st century. At a time when budget cuts to public safety have forced departments to think more carefully about where they devote resources, evidence-based policing offers to ensure the cost-effectiveness of new technologies and methods. Perhaps more importantly, it also promises to increase the transparency and accountability of law enforcement, especially in the wake of recent high-profile — and sometimes fatal — police-civilian encounters.

Space and Place

“I look at it from a medical perspective — you had an infection, we put some ointment on it, and now the infection is gone,” says Christopher Herrmann, assistant professor in the Law and Police Science Department at John Jay College. “That’s what evidence-based policing is all about — find the problem, try to solve it, and show that your solution worked.”

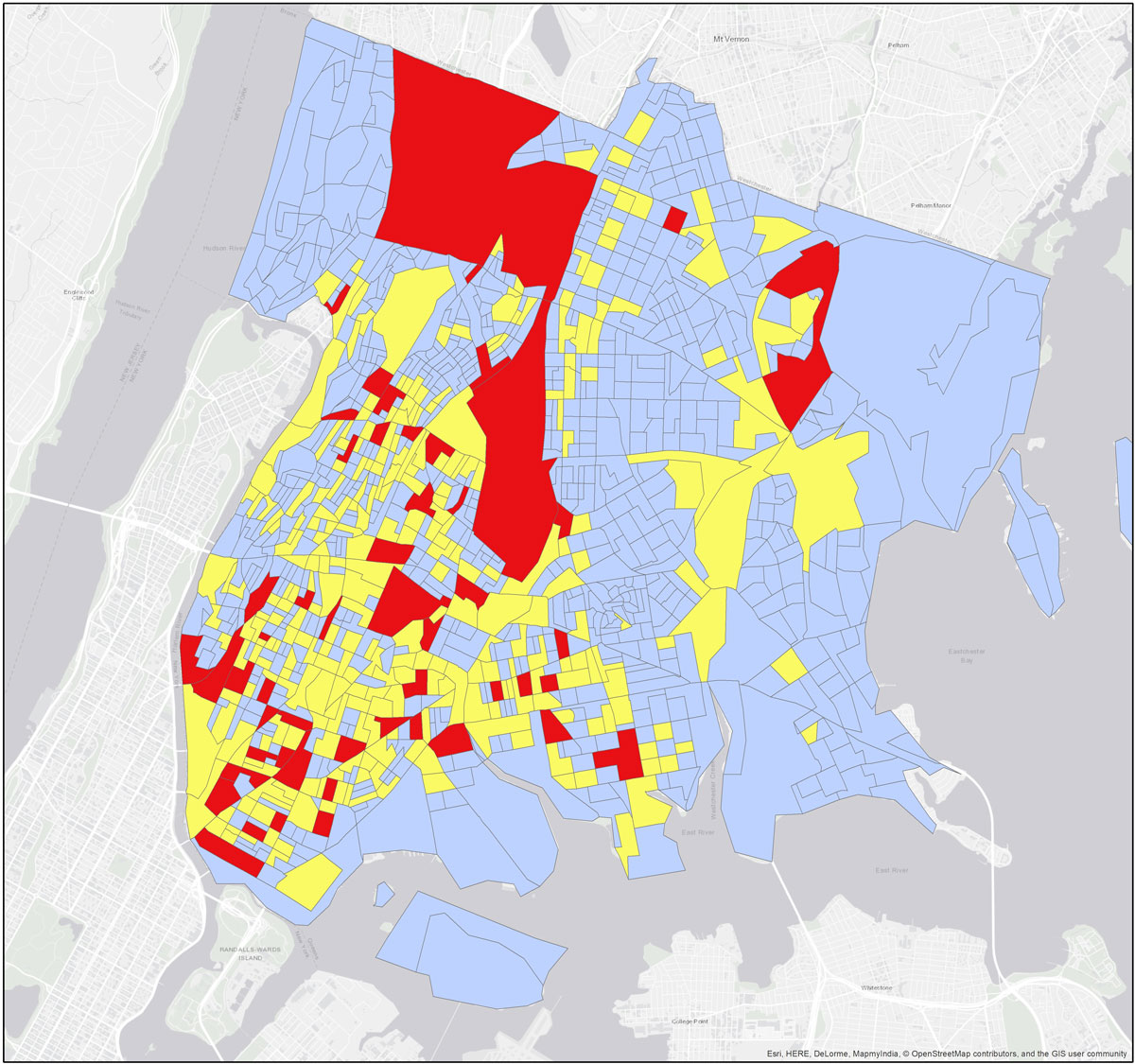

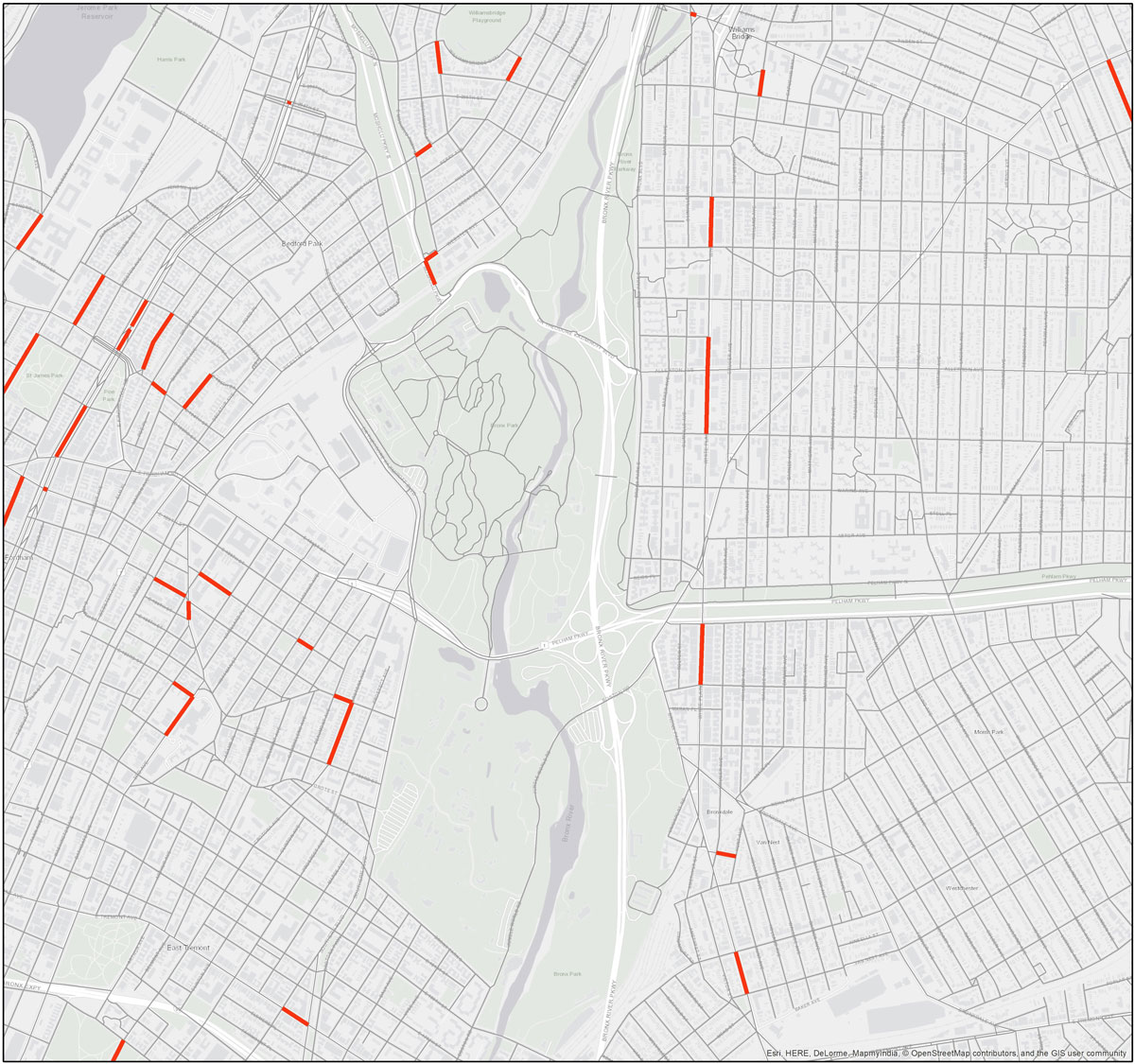

Herrmann is one of the figures at John Jay — and beyond — helping to move the needle in this area. A former crime analyst with the NYPD, his work can be seen as a continuation of the kind of spatial analysis begun under Compstat, which reinforced the idea that crime is not ubiquitous, but tends to cluster in small geographic units. Knowing where those clusters occur — and when, as crime often takes place during predictable timeframes in such areas — is key to the “hotspot” strategies that make up much of evidence-based policing.

Since crime committed in these hotspots can have ripple effects across a neighborhood, locating and proactively patrolling them could lead to widespread reductions. But as Herrmann also notes, it’s not always that straightforward. In the past, police might have labeled entire neighborhoods as hotspots — “just a big blob on the map,” he says — when in reality the crime was occurring on only a few problem street corners. What’s more, they might have only been looking at crime occurring in these areas in week or month-long intervals, ignoring the spatiotemporal shifts that were happening by the day or even the hour.

Herrmann has therefore focused on tracking what he calls the “micro-level” changes in crime hotspots. “For me, the process is the most important thing,” he says. “We say, okay here’s a problem, let’s zoom in on the problem. Then we see it’s not one big problem, it’s actually five small problems. Then we say, okay let’s zoom in on those.”

In his latest work, Herrmann has applied that analysis to the city’s public housing projects, working on a research team at the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) to study gun violence throughout its 328 developments. Using cluster maps and other Geographic Information System (GIS)-generated material, he looks at where gun violence hotspots overlap NYCHA developments across the city, and drills down to figure out exactly where and when gun violence is occurring.

What he’s found is that, just as in his other studies, crime is not spread evenly throughout the projects but is instead often concentrated in a just few problem units. In New York City as a whole, for example, an average of 12 out of 100,000 people become victims each year of gun violence; across the city’s public housing projects, that number increases to 68 out of 100,000. But there are some individual housing projects, he says, where the rate reaches a staggering 800 out 100,000.

Herrmann chalks this increase and its impact on the city’s overall average up to the 80/20 rule — or the mathematical principle that for many events, roughly 80 percent of the effects come from 20 percent of the causes. “So you have this one housing project where you’re literally 50-plus times more likely to get shot than the average New Yorker,” he says. “Obviously, that’s a problem.”

Crime hotspot maps are a critical tool for policing on a neighborhood level, allowing police to look at

where and when incidents are occurring and tailor prevention strategies accordingly.

The Human Component of Policing

But Herrmann doesn’t only track where and when crime is happening. He also examines the solutions proposed in response to it, whether they be public policy initiatives or new technologies. In the case of gun violence in public housing, these include continued backing of space-time crime analysis; improved lighting in and around buildings; and more cameras and ShotSpotter locations, which can help police thwart crime by alerting them to incidents happening in real time.

These latter technologies are of particular interest to Eric Piza, associate professor in the Department of Criminal Justice, and another faculty member leading the evidence-based policing effort. Like Herrmann, Piza’s resume straddles a unique border between analyst and academic — he too has served as a crime specialist in operating police departments, including as a GIS specialist in Newark, New Jersey. (Because there are only a few people in the criminal justice world with GIS expertise, Piza and Herrmann have been asked by the International Association of Crime Analysts to collaborate on a training manual to share their expertise.)

“One of my favorite analogies is that police like to use all technology like a refrigerator — they plug it in, make sure it’s running, open the door, close it, etc.,” Piza says. “But if you’re trying to do something as complex as prevent crime with technology, it’s not quite as straightforward.”

Figuring out what impact, if any, those technologies have on crime reduction is another major part of evidence-based policing. Much attention in recent years has been paid to the use of body cameras, for example, which have been heralded as a way to both deter crime and to increase the overall transparency and accountability of law enforcement in the wake of controversial police-on-civilian shootings. In theory, experts argue, these devices should work, on the principle that people behave better when they think they are being watched.

In reality, the results are a little more ambiguous. Last year, a major review of the use of body cameras in Washington, DC found they had little discernible effect on police-civilian interactions, with officers wearing the device facing complaints at about the same rate as officers without them. Those findings have led some to question whether the recent surge in body camera investment — following the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO in 2014, the federal government alone spent $40 million in an attempt to get departments across the country to adopt the technology — is worth it.

Piza, who has studied both body cameras and ShotSpotter technology, attributes findings like these not to the technologies themselves, which he says show obvious promise, but to their implementation. Officers and researchers are still learning the proper techniques for using cameras as a crime-deterrent tool, such as making sure the camera is visible on the officer’s body as well as announcing explicitly that they are wearing cameras when they arrive on a scene. Incorporating this knowledge in procedural justice trainings, he says, could go a long way toward maximizing effectiveness.

Piza calls these proactive efforts part of the “human component” of policing. “The technology itself is not going to prevent crime,” he says. “It takes the police using the technology in an evidence-based manner to generate the benefits that we anticipate.”

A Bird’s Eye View

Still, evidence-based policing doesn’t only deal with the kind of micro-level research in which Piza and Herrmann specialize. Just as crime analysts and criminologists are working to determine the efficacy of various strategies and technologies at the local enforcement level, evidenced-based policing also seeks to find out what effect state and national policy has on more general criminal justice issues.

This sort of analysis is the purview of people like Preeti Chauhan, an associate professor in the Department of Psychology and the director of the Misdemeanor Justice Project (MJP). The MJP seeks to understand the criminal justice response to lower-level offenses in New York City and elsewhere, using data analysis to produce reports on the fairness and effectiveness of various policies, and then disseminating its findings to the wider public. “We see it as providing a bird’s-eye view of what’s actually happening in the city,” Chauhan says.

MJP started in 2012, just as public outcry over New York City’s controversial “stop-and-frisk” policy was reaching a fever pitch. Advocates of the practice — which involves the broad-scale searching of pedestrians for weapons — believe it’s an effective strategy for reducing crime in neighborhoods. But critics argue that its impact is overstated and, perhaps more concerning, that it encourages racial profiling by law enforcement; in 2017, almost 90 percent of individuals stopped were African-American or Latino, and the vast majority of searches turned up no weapons or other contraband.

For Chauhan, the controversy highlighted a gap in the academic literature. At a time when much of the focus in the wider criminal justice arena was on violent crime, Chauhan realized that little attention was being paid to lower-level offenses, such as misdemeanor arrests and criminal summonses. “The idea was that there were all these other touch points between police and communities that weren’t getting documented that were really high volume,” Chauhan says. She added that the 2014 deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner at the hands of police helped further emphasize the importance of these “everyday encounters.”

Since then, MJP has produced reports on a wide range of low-level enforcement issues, from pre-trial detention to incarceration rates. In 2015, it released one of its most significant analyses, which found that misdemeanor arrests, criminal summonses, and pedestrian stops had decreased by 61.5 percent since 2011. The biggest drop, however, was in street stops — a 93 percent decline between their 2011 peak and 2014. The fact that this decline accompanied a continued drop in NYC’s crime rates suggested that critics of the city’s stop-and-frisk policy, which was ruled unconstitutional and discontinued in 2013, may have been correct.

Chauhan says the findings of that report made up part of the foundation for the city’s Criminal Justice Reform Act, a landmark piece of legislation passed last year that directs police to issue civil summonses, rather than criminal ones, for petty offenses such as public urination and littering. MJP, with the help of funding from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, is replicating its model through a research network that now includes cities like Los Angeles, Toledo, and Louisville.

Though MJP doesn’t make policy recommendations based on its findings, Chauhan says she hopes the group’s work will encourage criminal justice stakeholders to ask “what’s the point” of existing policies and policing strategies.

Racism and Accountability

Chauhan’s focus on misdemeanor arrests demonstrates the potential for researchers who may have even more specific targets in mind. As violent encounters between police and citizens continue to capture the public’s concern, some experts are turning their attention to the social aspects of policing – including the ways in which police behavior, as well as police-community relations, affect law enforcement work.

One of the most prominent of these researchers is Dr. Phillip Atiba Goff, inaugural Franklin A. Thomas Professor in Policing Equity at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and co-founder of the influential Center for Policing Equity. A 501(3) research center and think tank established in 2006, the CPE brings together law enforcement agencies and leading researchers to study the social components of policing, using big data to show how various factors – such as racism and bias, job stress, and other psychological issues – influence the way police treat and respond to different communities. In doing so – and in keeping with wider evidence-based efforts –CPE strives to provide a scientific basis for reforms in police departments around the country.

To this end, one of the tools Goff and his team at CPE have helped develop is the National Justice Database, a National Science Foundation-funded effort that tracks and compiles statistics specifically on police behavior from around the country. Spurred by police shootings like that of Michael Brown in Ferguson and the recognition among law enforcement officials and other experts that no national repository of such incidents existed, Goff and CPE launched the project in 2014. Since then, they’ve worked to standardize and analyze data on things like police stops and use of force incidents.

The NJD has already begun to provide some answers to fundamental questions around justice and equity in policing. In a study that used statistics collected through the database, the CPE found in 2016 that, although police officers employ force in less than 2% of all police-civilian interactions, the use of that force is more than three times higher for African Americans than for whites. (The study notes that this discrepancy remains even when racial disparities in crime are taken into account.) For Goff and others, the results confirmed a long-held suspicion: that racism and bias do in fact play an important part in police behavior.

Much if not most of this bias, according to Goff, is implicit rather than expressed openly. “Ninety percent of behavior is driven by how we react to situations, not by attitudes. The question is how to reshape situations so that fear or dislike of black people does not produce an armed response.”

The database isn’t the only initiative CPE has undertaken in their mission to address racism in law enforcement. Goff and his team are working to apply the tools and strategies of Compstat to policing equity and accountability, combining the aforementioned information with census data and geographic markers to systematically target those factors that a department can control, such as problematic police behavior. In a way, the center’s work represents a kind of next step in Compstat’s evolution, as well as the evolution of evidence-based policing at large: to improve policing practices not only by better utilizing technology and resources, but by examining and strengthening the very relationship police have with the people they’re meant to serve.

Photos: Getty (header), Pap Studio (portraits)

“We say, okay here’s a problem, let’s zoom in on the problem. Then we see it’s not one big problem, it’s actually five small problems. Then we say, okay let’s zoom

in on those.”

—Christopher Herrmann,

Assistant Professor

Psychologist Preeti Chauhan reaches beyond the confines of her discipline to lead the Misdemeanor Justice Project (MJP), producing data on the under-examined touchpoint that make up much of the criminal justice system’s day-today activity.